Block Quote

This project was built on the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and the Mississaugas of the Credit first nation as well as on top of the buried Taddle Creek. This Indigenous landscape project hopes to honour Taddle Creek while creating an outdoor space where the Indigenous community may gather and see themselves represented on the University of Toronto campus. We are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land.

The Indigenous Landscape at Taddle Creek enhances Indigenous representation on colonized land, supporting the University of Toronto’s response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s Call to Action. Also named Ziibiing, meaning “river” in Anishinaabemowin, the project integrates elements that reflect Indigenous cultural practices and knowledge.

Characterized by themes of Indigenous landscape design, community representation, and the healing power of water, the design acknowledges the historical significance of the buried Taddle Creek below the surface, once a vital resource for Indigenous communities.

The project aimed to create a space that acknowledges and facilitates Indigenous cultural representation, history, and teachings. Led by Brook McIlroy’s Indigenous Design Studio, the design was shaped through extensive consultations with Indigenous elders and stakeholders, reflecting a broad spectrum of Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices.

Through consultation with Indigenous groups, the importance of Indigenous spaces on campus was affirmed as a unifying theme. A 2017 report by the Steering Committee for the University of Toronto Response to the TRC of Canada further established that physical space is central and symbolic to Indigenous communities, and that the current spaces dedicated to Indigenous experience at the University were lacking in both number and features.

“THE IMPETUS FOR THE PROJECT WAS: HOW DO WE GET MORE INDIGENOUS REPRESENTATION IN SPACES THAT ARE IN OTHERWISE COLONIAL INSTITUTIONS? AND DOING SO IN CONSULTATION WITH ADVISORY COMMITTEES AND ELDERS TO IMPROVE NOT ONLY VISIBILITY BUT ALSO OPPORTUNITIES FOR OUTDOOR EDUCATION, TEACHING AND LEARNING EVENTS, AND TO REALLY BRING INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE TO THE FOREFRONT OF THE CAMPUS.”

- Ryan Gorrie, Principal, Brook McIlroy Indigenous Design Studio

Taddle Creek historically flowed through the heart of what is now Toronto. Prior to colonization, it provided water, food, and a transportation route to Indigenous communities. The creek also supported early colonial industries. As Toronto grew, industrial and residential waste polluted the creek, making it a public health hazard. By the mid-1880s, Taddle Creek was buried and converted into a sewer system.

One of the main challenges was designing a space that held rich meaning for multiple First Nations stakeholder groups with different histories, cultural practices, and teachings. Brook McIlroy adopted a thematic approach that allowed for specific representational design while remaining open to interpretation by various Indigenous communities.

“THE BURYING OF THE LAND AND WATERS OF TADDLE CREEK WAS SYNONYMOUS WITH THE BURYING OF INDIGENOUS CULTURE AND THE PEOPLE WHO USED THOSE FOR SUSTENANCE.”

– Ryan Gorrie, Principal, Brook McIlroy Indigenous Design Studio

One of the main challenges was designing a space that held rich meaning for multiple First Nations stakeholder groups with different histories, cultural practices, and teachings. Brook McIlroy adopted a thematic approach that allowed for specific representational design while remaining open to interpretation by various Indigenous communities.

“WE WANTED TO FOCUS ON BIG THEMES LIKE THE COSMOS IN TERMS OF STAR KNOWLEDGE, PLANTINGS WHICH WERE NATIVE TO THE AREA, THE SYMBOLIC USE OF FIRE AND WATER, AND OTHER THEMES THAT COULD BE SPOKEN ABOUT BY FIRST NATIONS. DESIGN ELEMENTS CAN HAVE MULTIPLE MEANINGS AND I THINK THAT THERE’S ACTUALLY POWER IN AMBIGUITY BECAUSE IT ALLOWS INTERPRETATIONS TO BE MULTIPLE AND TO AFFECT PEOPLE IN DIFFERENT WAYS.”

– Ryan Gorrie, Principal, Brook McIlroy Indigenous Design Studio

Water, symbolizing life and healing, played a crucial role in the design. “Water and specifically Taddle Creek itself was the biggest influence in terms of the design because water is life, as we know,” recalled Gorrie. “The late Lee Maracle, who was one of the advisers on this project, has written extensively about water and our relationship with water. She really challenged us to bring that to the forefront.”

“WE DO NOT OWN THE WATER, THE WATER OWNS ITSELF. WE ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR ENSURING THAT WE DO NOT DAMAGE THE WATER. WE DO NOT HAVE AN ABSOLUTE RIGHT TO USE AND ABUSE THE WATER; WE MUST TAKE CARE OF THE WATER AND ENSURE THAT WE HAVE A GOOD RELATIONSHIP WITH IT. THIS RELATIONSHIP IS BASED ON MUTUAL RESPECT.”

– Lee Maracle (Downstream: Reimagining Water, 2017)

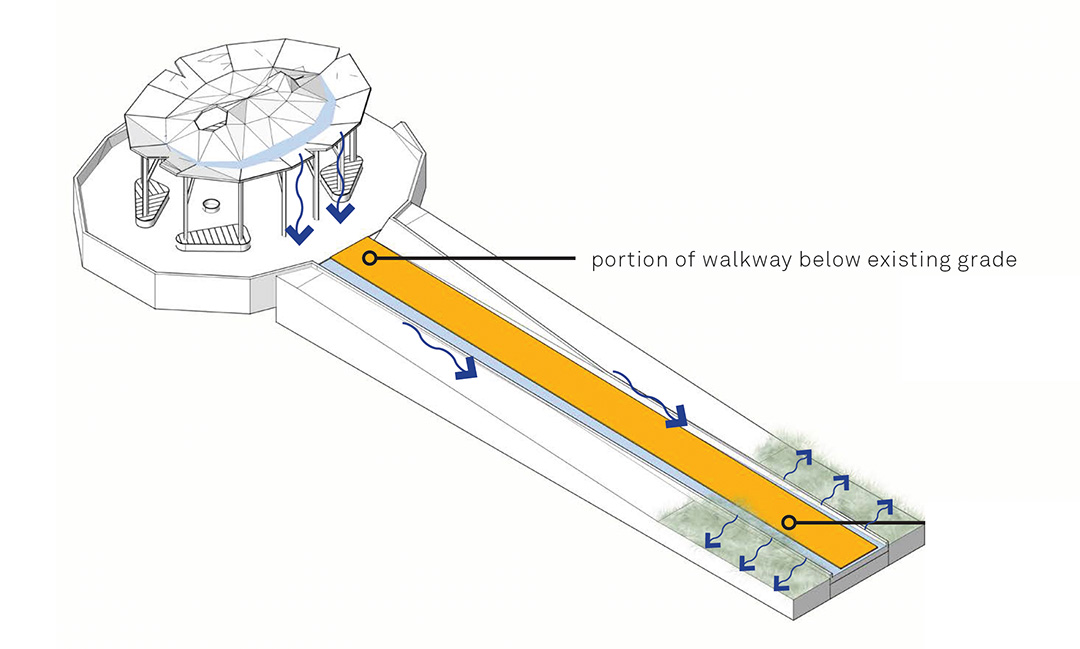

The designed landscape evokes the presence of the creek below. The central Knowledge House canopy is made of bronze, incorporating the ceremonial material copper as a vessel for water. Rainwater comes off the canopy and is captured by a water feature which directs it towards rain gardens. The rain gardens themselves are at a lower grade, near where the creek likely would have been.

The design aimed to create spaces for passive and active learning opportunities, integrating outdoor classrooms, storytelling areas, and flexible event spaces. The goal of these spaces is to promote teaching and learning with a focus on Indigenous knowledge and stories.

The project team made a concerted effort to use Indigenous-owned resources where possible. The original request for proposal (RFP) from the University of Toronto included a requirement for an Indigenous designer to be part of the team. Brook McIlroy’s Indigenous Design Studio is well-suited to address these types of project requirements and in turn prioritizes working with Indigenous businesses to bolster representation in the architecture and construction industries.

The design placed a strong emphasis on accessibility and sustainability. The University of Toronto’s strict accessibility standards required materials and pathways that are easy to navigate and promote inclusivity. Sustainability was also an important factor considering the natural, cultural, and historical setting of the project. This necessitated the inclusion of locally-sourced materials where possible.

Materials selected for the landscape at Taddle Creek were the result of thoughtful and intentional design choices considering many factors, chief among which was the power in materiality. The materials themselves form part of the representation and storytelling of the First Nations.

In terms of surfacing materials, the design team selected natural materials where possible to respect the environment and cultural context of the project site. At the same time, the surfacing materials had to fit the aesthetic and functional requirements of the on-campus project.

“THE SITE DESIGN PROPOSED LOW IMPACT DEVELOPMENT PRACTICES THROUGHOUT INCLUDING MANAGING STORMWATER ON SITE BY THE INTRODUCTION OF RAIN GARDENS AND THE USE OF NATURAL AND PERMEABLE PATHWAY SURFACING SOLUTIONS. ACCESSIBILITY WAS ALSO A CRITICAL ELEMENT, AS THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO HAS TIGHT ACCESSIBILITY DESIGN STANDARDS. LIMITING THE EXCAVATION AND GRADING REQUIRED, WHILE MAKING THE PATHWAYS FULLY AODA COMPLIANT AND PERMEABLE LED US TO SPECIFY STABILIZED AGGREGATE.”

– Luke Mollet, Senior Landscape Designer and Project Manager, Brook McIlroy

Another consideration was integrating natural elements within the campus context. The materials chosen had to cater to the practical needs of an urban university while fostering a connection to nature.

“WE DIDN’T WANT TO HAVE THIS PLACE ENTIRELY PLAZA OR ENTIRELY GREEN; IT HAD TO FUNCTION, HAD TO BE DURABLE, BUT WE ALSO WANTED NATURALIZED AREAS. THAT’S WHERE THE AGGREGATE COMES IN – IT PROVIDES A BRIDGE BETWEEN URBAN TRAIL ACCESSIBILITY AND THE PERMEABLE NATURAL MATERIAL.”

– Ryan Gorrie, Principal, Brook McIlroy Indigenous Design Studio

These factors led to the selection of stabilized aggregate as the surfacing material for the amphitheatre teaching space and the pathways throughout the site’s naturalized areas.

Organic-Lock Stabilized Aggregate (OLSA, known for its superior performance) was the selected stabilized aggregate option to meet design criteria.

Envirobond, the creator of Organic-Lock, is a proudly Indigenous-owned company founded on the principles of environmental stewardship and innovation. Organic-Lock is an organic aggregate binder that locks particles in place, providing both a natural aesthetic and effective erosion control for permeable pathways, trails, and other landscape surfaces. The company is deeply committed to supporting Indigenous projects and communities by providing sustainable products, extensive technical support, and project oversight, while also partnering with industry leaders to fund Indigenous landscape initiatives. The decision to incorporate OLSA for natural pathways was informed by multiple factors.

1- Natural Aesthetic: the natural look of OLSA aligns with the project’s emphasis on integrating natural elements into an urban setting.

2- Accessibility the University of Toronto’s strict accessibility standards necessitated a material that was stable and easy to navigate. OLSA provides superior strength and durability to stand up to high traffic volumes expected on campus and to provide accessibility for all.

3- Permeability: OLSA surfaces are permeable, helping with stormwater management and supporting low-impact development goals.

4- Local Sourcing: the OLSA for this project was supplied by Lafarge Canada with a traveled distance of approximately 25km from the production facility to the project site. The total traveled distance from quarry to project site was approximately 75km.

5- Indigenous Sourcing: Organic-Lock is an Indigenous-owned company, with CEO Mike Riehm having family roots with the Mohawks of Kahnawake, a Mohawk first nation in Quebec, Canada. While the material selection team was unaware of this Indigenous connection at the time of procurement, this added a meaningful layer to the project. Organic-Lock collaborates closely with partners like Lafarge Canada to provide specific technical support and oversight for Indigenous projects. Additionally, Organic-Lock works alongside their dealers to support indigenous projects through financial product discounts, reinforcing their commitment to Indigenous communities and sustainable development.

Aggregate Photo Courtesy of Organic-Lock supplied 86 metric tons (95 short tons) of OLSA in Dundas Blend to cover approximately 3125ft² (290m²) of foot-trafficked pathways at the Indigenous Landscape at Taddle Creek project.

The planning and installation stages were marked by close collaboration between project stakeholders.

Lafarge Canada and Organic-Lock provided on-site support for the installation of the OLSA pathways. OLSA was delivered by Lafarge pre-mixed with water, streamlining the installation process, ensuring consistency in hydration levels, and reducing the potential for errors.

The OLSA pathway mock-ups revealed complications with the edging design, originally raised aluminum, which impeded the use of rollers for proper compaction and had the potential to impede water shed off of the surface. On-site adjustments were made in consultation with the Organic-Lock team to revise edges to a tapered design.

“CHANGING THE EDGE TYPE WAS CRUCIAL FOR ENSURING PROPER COMPACTION, EFFECTIVE WATER MANAGEMENT, AND LONG-TERM DURABILITY OF THE PATHWAYS. THIS ADJUSTMENT HIGHLIGHTS THE IMPORTANCE OF IN-SITU MOCK-UPS FOR LANDSCAPE PROJECTS TO IDENTIFY AND RESOLVE PRACTICAL CHALLENGES EARLY IN THE CONSTRUCTION PROCESS.”

– Mike Riehm, CEO of Organic-Lock

The Indigenous Landscape at Taddle Creek project faced a few challenges from concept design through to construction. Each required thoughtful solutions to ensure successful outcomes.

1- Consultation Process: Engaging a broad range of Indigenous stakeholders and integrating their diverse perspectives into the design was complex but ultimately rewarding. “The more you do this kind of work, the more you realize it gives you good feelings, but it also implicates you in your responsibility to the community, which is really humbling,” reflected Gorrie. This sense of responsibility was at the forefront of the consultation process and the overall design philosophy.

2- Custom Elements The design included numerous custom elements, such as reclaimed wood benches, bronze structures, and the Knowledge House and Cultural Markers, which required meticulous detailing and execution.

3- Urban Integration: Harmonizing naturalized elements with the urban campus environment required innovative solutions, particularly for stormwater management and accessibility. Material selection was key in striking this balance.

4- On-Site Pathway Edge Adjustments: During the construction stage, an on-site OLSA pathway mock-up revealed an unsuitable aluminum edge condition. In close collaboration with Brook McIlroy, Lafarge Canada, and Organic-Lock, the installing contractor was able to revise the edge condition to a tapered design, allowing for effective compaction and surface water management.

Completed in September 2023, the Indigenous Landscape Project at Taddle Creek successfully enhances Indigenous communities’ visibility and representation on the University of Toronto campus through physical space. The design’s acknowledgment of Taddle Creek and the incorporation of water as a healing element reflect a profound connection to the site’s history and Indigenous culture.

The collaborative design process integrated Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices, ensuring that the project reflects a true partnership with Indigenous communities. The site itself provides opportunities for education and storytelling through the incorporation of thematic natural elements that everyone can connect with. The low-impact development approach taken aligns with Indigenous communities’ respect for the natural environment while ensuring accessibility for all.

While this project is a significant step forward, it also acknowledges that much work remains to be done in the ongoing journey toward reconciling our colonial past through meaningful representation, acknowledgment, education, and action.

Brook McIlroy – https://brookmcilroy.com/projects/service/indigenous-design-studio/

LaFarge Canada – https://www.lafarge.ca/en

Organic-Lock – www.organic-lock.com